The Power of Collaboration for Water Quality Improvement

Purpose:

A case study of a participatory, collaborative initiative to improve river water quality in Ireland.

Location:

Lilliput bathing waters and Dysart Stream, Lough Ennell, Co. WestmeathÂ

Participants:

Local Authority Water Programme (LAWPRO), Teagasc Agricultural Sustainability Support Advisory Programme (ASSAP), 23 local farmers and the Water European Innovation Partnership (EIP)

Presented by the WaterMARKE research project and CAP Network Ireland

1. Introduction & Background

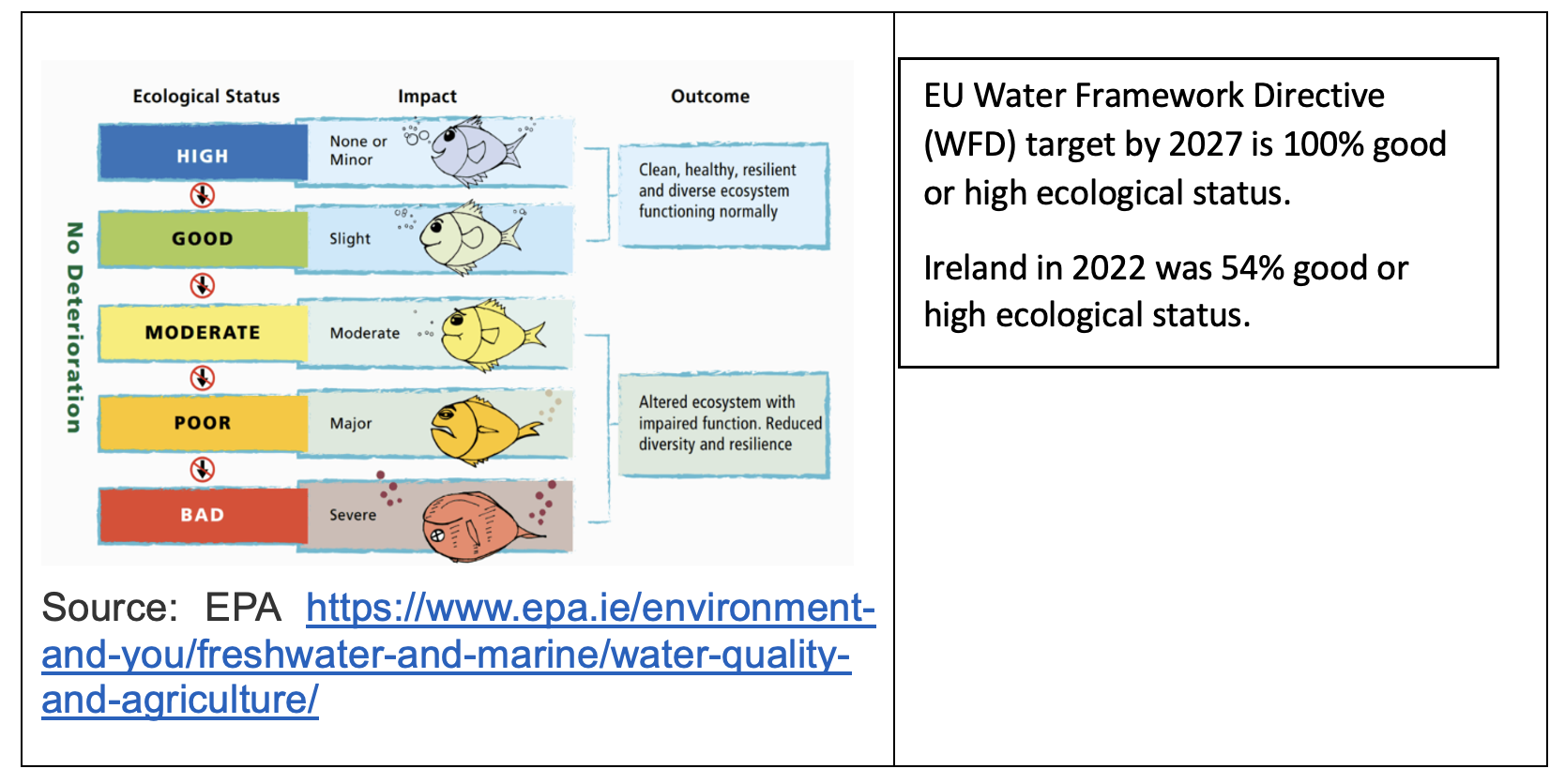

Under the Water Framework Directive, all EU member states must achieve ‘good’ water quality on an ecological scoring system from (1 – ‘bad’) to (5 – ‘very good’). Many EU countries are lagging behind targets, with Ireland currently having 54% of waterbodies at ‘good’ (4) status. See below the ecological status categories ranging from ‘bad’ to ‘very good / high’.

As agriculture is Ireland’s largest land use, it is unsurprising that it is a significant pressure on rural water quality. This case study describes the collaborative approach undertaken to mitigate negative impacts of losses of nutrient and sediment on the ecology of the Dysart river, with subsequent negative impacts on bathing waters at Lilliput beach on Lough Ennell.

The collaboration to improve water quality on the shores of Lough Ennell is an inspiring example of how scientific research, effective engagement with farming communities, and targeted action at the source of pollution to implement ‘the right measure in the right place’, can reverse negative water quality trends in problematic areas.

2. Developing the ‘System’ to Improve Water QualityÂ

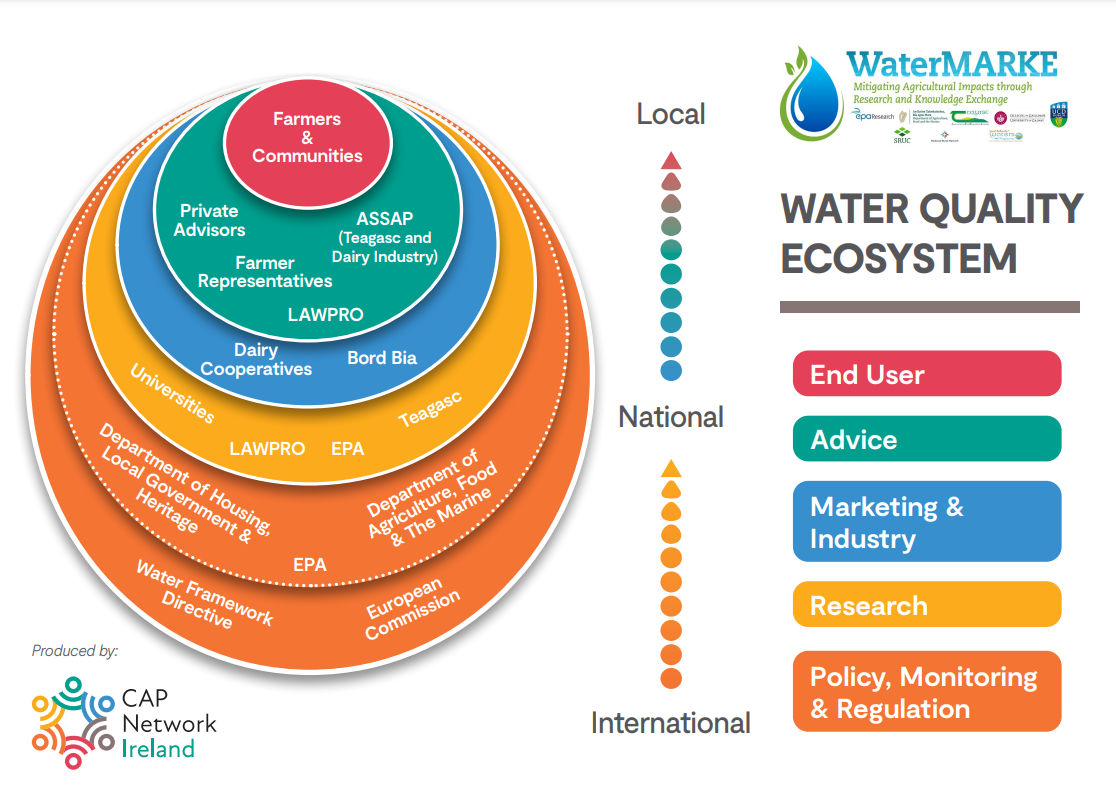

In the background, many stakeholders across policy, regulation, research, knowledge, marketing and industry have been working increasingly closely in recent years to tackle water quality problems. Strong linkages have been developed between government departments with responsibility for local authorities (who are responsible for Water Framework Directive (WFD) reporting) and agriculture, enabling the development of new and innovative structures. The Environmental Protection (EPA) undertakes both monitoring of water quality for WFD reporting and catchment-level risk mapping. Based on EPA monitoring data, Priority Areas for Action (PAAs) were identified in consultation with local communities. See the below diagram highlighting the water quality innovation ecosystem for farm water quality improvement in Ireland.

Ongoing research on agricultural impacts in the Teagasc Agricultural Catchments Programme, EPA and Universities has informed the need for localised information, as the pathways of loss of farm nutrients /sediment to water and the resulting impacts on water quality, vary with soils, geology, rainfall, slope and farm systems.

Addressing the need for localised information, the Local Authority Waters Programme (LAWPRO) was established in 2018, staffed with a team of Catchment Scientists and Community Water Officers to provide catchment-level scientific information and increase community awareness of problems and solutions.

These localised impacts also call for localised advice to tackle impacts across different farm contexts. In response to this need, the Agricultural Sustainability Support Advisory Programme (ASSAP) funded by Teagasc and Dairy Industries Ireland, currently have a team of 36 dedicated water quality advisers to work with farmers on specific at-risk waterbodies in designated PAAs.

Where LAWPRO identify agriculture as a significant pressure within a PAA, information on the specific issue is referred to the local ASSAP adviser. ASSAP advisers then work with farmer groups and individually with farmers, undertaking farm assessments to help the farmers to implement the ‘right measure in the right place’.

Thus an ‘innovation ecosystem’ has developed across a wide range of stakeholders that has facilitated a network of integrated, innovative structures to collectively improve water quality.

3. Identifying The Source of the PollutionÂ

EPA monitoring of the bathing waters at Lilliput indicated an increasing trend in pathogens, linked to animal wastes, which placed the bathing waters at risk of being declared unsafe for bathing. The closest contributing stream to the bathing location is the Dysart_010 which EPA monitoring also showed to be at moderate ecological status. The Dysart_010 was designated a Priority Area for Action under the second National River Basin Management Plan. As a result LAWPRO undertook a scientific investigation into the pressures impacting both the stream water quality status and also the bathing water status.

The approach adopted around Lough Enell in Co. Westmeath highlights how poor water quality can have an effect on an entire community and why it takes community action to fix it. Joan Martin, LAWPRO Catchment Scientist, outlines how Lough Ennell was designated a priority area by Westmeath Local Authority (County Council) and selected as an area for action by LAWPRO. “The Dysart Stream was selected as a Priority Area for Action (PAA) under the Second Cycle of the River Basin Management Plan because it was thought to be polluting Lilliput bathing waters†she explains. Lilliput Adventure Centre is a local water sports activity centre that was in danger of being closed down due to increasing levels of pathogens detected in the lake.

Before action could be taken, a scientific investigation was needed to identify the exact location and source of these pathogens. Joan says, “LAWPRO undertook a desktop assessment and assessed the status of the river, looking at the biology, chemistry and all information available.†The source of the problem was soon identified. “We found that (the Dysart Stream) was not meeting its ecological objectives of ‘good’ water quality and we were having agricultural pollution in the stream. Excess phosphorous and sediment were causing water quality issues.â€

Although the upper catchment of the stream had ‘good’ water quality status, the lower part of the stream where it entered the lake was deemed ‘moderate’. Animal faeces were identified as the source of the pathogens, which meant that cattle slurry was escaping from local farms to the stream feeding into the lake. “Once we were aware of that, we carried out macroinvertebrate assessments and we walked certain sections of the river and pinned down the areas that we thought were more problematic than others. We referred these to the local ASSAP Advisor to engage with the farming community in these areas.†A PAA meeting was called with local farmers on the 1st of July 2019 and the work to improve water quality in Lough Ennell began.

4. Mobilising The Local Farming Community

David Fay, who farms on the shores of Lough Ennell, remembers the meeting well, “Joan Martin asked if I would engage, and I agreed. All the local farmers came together, and Joan highlighted that the quality of the water was dropping and suggested different measures that we could take.â€

Once the local farmers became aware of the problem, David Webster, the local ASSAP adviser based in Teagasc offices in Mullingar became involved. “My role is to engage with the farmers in the PAA both as a group and as individuals.†He explains, “we highlighted the general issues in the PAA first of all, and then that would have been backed up by individual farm visits where we would have identified individual measures that need to be improved on farms.â€Â

5. The Remedial Measures Begin to Work

David Webster explains how he and 22 other farmers worked together to find solutions. “It was identified that slurry spreading at certain times of the year can be an issue with pathogens in the stream and also cattle access points; cattle drinking in the stream. In the case of the lake here, under good farm practice (Good Agricultural Practice Regulations), the farmer is obliged to keep 20 metres back from the lake, but I felt that the 20 metres wasn’t sufficient.â€

ASSAP advisers have observed instances where the most impactful farm-level actions that benefit catchment-level water quality, can prove costly for individual farmers. Recognising this challenge, the Water European Innovation Partnership (EIP) project (which in itself is a sector-wide collaboration), can provide funding to design and implement measures to address challenges in collaboration with farmers. Here we see an example of where the provision of solar-powered cattle drinkers on farms where cattle are excluded from rivers has catchment-wide benefits.

David Fay picks up the story concerning his own farm, “my problem here was that the cattle were going into the river to drink. I fenced off the drinking points and put in a solar pump to pump the water out of the river rather than letting the cattle into it.†He is delighted with the results, “the water system going in has been a huge improvement. We now have a water system where we didn’t have one before and we now have troughs all over the farm.â€

Not only has this given more options and flexibility for his grazing strategy, but it has also made David’s life easier. “I can split fields four ways now. We used to be guided by the fields and the drains and where animals could get in and out. We were constantly fencing because of cattle breaking them down.â€

David is now so committed to playing his part in improving local water quality that he is prepared to go the extra mile. “Because I am so close to the lake, I keep back 100 metres as a buffer zone for slurry. All the dry drains, I am keeping back into the field because (this area is) so sensitive to slurry. We’re keeping back about 30 metres.â€

He agrees that it is very important to get the spreading of slurry right. “You have to be very mindful of the weather conditions, the height of the grass and the time of the year that you are doing it. With the weather, that can be challenging but it’s challenging for everyone,†he concludes.

6. Conclusion

At the core of this case study is the unique relationship between LAWPRO Scientists and Community Officers and ASSAP advisers who foster individual relationships with the landowners who are working hard to put remedial actions in place.

Farmers were understandably cautious when first approached. “Initially you would be afraid in case you’d be getting the blame,†says David Fay, “but then when you start engaging with them (LAWPRO and ASSAP staff), they were grand, no problem at all when doing the tasks.†David and the other farmers on the Dysart stream now recognise the beneficial outcomes of their involvement in the WaterMARKE project. “When you work with it and get into the idea that the water quality is deteriorating in the country, these things do work and we are making a difference,†David concludes. He also highlights the impact of the WaterMARKE project and how it “seems to have worked well with the water quality overall, and the other farmers seem to be quite happy.†Today, numerous farmers have improved their farm infrastructure, and they are perceived as contributors to solutions rather than contributors to problems within the community.

The WaterMARKE research project has chronicled the development of an innovative, collaborative and participatory innovative approach to water quality improvement across Ireland. The high level of engagement of farmers with the ASSAP programme has also provided a valuable research opportunity to examine the socio-economic and behavioural drivers of the high adoption rates of water quality mitigation measures. Publication and further details are available here.